On genetic testing: does the pet genetic testing industry need rules and regulations?

There has been increasing concern about pet diagnostic testing in the last year or two. Why would there need to be regulation in the pet genomic testing industry? As long as you get reasonably accurate results, why would it matter that there were standards upheld and regulations met?

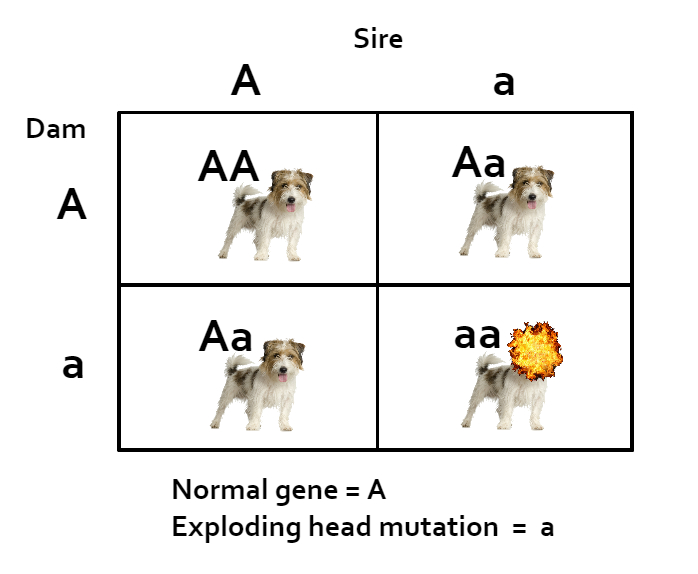

Imagine a scenario where an owner tests her dog with one of the popular large panel tests, and she receives the results and is overjoyed. Her dog tests “clear” of 150 diseases! How exciting! She likely does not realize that only a handful are actually mutations found in his breed. However, let’s imagine that one of the tests is actually important for his breed. We here at the BetterBred blog like to use the fictional recessive mutation for “exploding head disease” as an illustrative example. So let’s say her dog came back “clear” for that mutation. He is a handsome dog, so after he was fully health tested and advertised as clear for 150 diseases, he was bred a few times. Since the disease mentioned is common in the breed, let’s say that a couple of the bitches he was bred to were carriers of the disease gene. Normally, breeding a carrier for a recessive mutation to a clear is fine because none of the puppies will ever have the disease. However, the “clear” result he received from his large panel test just happened to be inaccurate, and he was actually a carrier. Now all the puppies with dams who were also carriers have a 1 in 4 chance of having exploding heads – and some no doubt will, when breeders felt they were doing all they could do to keep their puppies healthy. What a heartache for breeders who were trying to do the best by their dogs, their puppies and their breed!

Here is another real scenario, the reverse of the last: imagine a new Toy Poodle bought for a breeding program was tested for the same large panel of 150 diseases, and found to be a carrier for a mutation associated with risk for the heart disease DCM (dilated cardiomyopathy) in a single breed, the Doberman, a mutation that is not known to increase risk in other breeds, even those with DCM common in the breed. Never mind that Toy Poodles rarely, if ever, have DCM, this new owner is immediately alarmed that a dog sold for breeding stock had parents that had not been tested for this disease and felt she was sold a faulty puppy. Now she’s on social media, upset and angry and is advised to seek retribution from the puppy’s breeder. This reaction is not a surprise, and it’s not the fault of the new owner that her dog was tested for this in the first place. How is she to know that this gene is not even confirmed to be causative for this disease in the breed at risk! Is it ethical that the Toy was tested for this disease, and told her dog may be at risk for heart disease? Now, because the company that makes the test assures everyone of their expertise, this new owner is going to spend 15 years or more wondering if her dog will develop heart disease for no reason. Most likely she will not take a chance on breeding this dog, so an otherwise perfectly healthy dog may be removed from a gene pool for no good reason. Fortunately Toy Poodles have ample diversity, but there are many breeds that cannot afford to have healthy dogs removed from the gene pool based on faulty scientific advice.

A minimal standard for quality in testing is needed as breeders use the information from genetic testing to make breeding choices and irreversible decisions regarding spay, neuter or euthanasia.

Shaffer, LS 2019

Such an occurrence may be rare, but with millions of dogs bred and sold every year, even a very low error rate translates into a great many real life problems. A 3% error rate means that for every 100,000 dogs tested, 3,000 of them will have inaccurate results. That’s a lot of breeding programs, and a lot of puppies who might suffer. Indeed, both situations described above have already been seen, and we likely will hear about similar situations again. Breeding decisions, or pet owner decisions about their beloved pets, like in the case of a pug in this article from Nature last year, need to be based on assuredly accurate results.

The pet genomics industry needs regulations

The following is a summary of a paper published in Human Genetics earlier this year by Lisa Shaffer PhD, a well published human geneticist and owner of PawPrints Genetics, and her team. The point? To offer guidance and suggestions based on human genetics protocols on self-regulation of the pet genomic industry, which is growing rapidly.

One positive aspect of the direct-to-consumer large panel tests (or large SNP chips that report on 150+ diseases): they serve as a repository of data to seek disease mutations. This, when researchers are capable of finding the mutations, can not only prove useful to canines, but also a model for human diseases. However, as noted in this paper: “some mutations can remain elusive and difficult to identify in this model organism.” In fact, because the canine genome comprises over 2.8 billion base pairs of DNA, finding mutations can be like looking for a needle in a haystack. When diseases are complex – meaning they require more than one gene to cause expression of disease, or when diseases are incompletely penetrant (disease severity and age of onset vary) or when mutations are fixed in a breed (nearly all the dogs have them) it can be even more difficult to find mutations. That is why research often takes many years and often remains unfruitful.

Currently, there is no regulatory oversight for canine clinical genetic testing and no consistency regarding quality assurance within the testing community. The purpose of standards and guidelines is to provide uniformity and guidance towards quality improvement across laboratories in the industry.

Shaffer, LS 2019

What sort of regulations should there be?

This article calls for a voluntary adherence to particular protocols within the pet diagnostic industry, based open similar recommendations from the the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Some aspects it outlines include requirements for personnel, workspace, quality practices, privacy, analytical validation, clinical validation, pre-analytical validation, analytical standards, and post-analytical standards. Phew….that’s a lot!

The following are key points:

Quality practices: Testing should include multiple methods to ensure accurate results. This means that the animal’s samples are tested twice, using different methods, so that if the two results conflict, the sample can be tested a third time to verify whether the dog has the mutation or not. This is why diagnostic testing from certain labs is so much more expensive than the large panel tests. Their error rates, therefore, should be far lower.

In the absence of an external proficiency program, implementation of a method-based proficiency testing (Schrijver et al. 2014) protocol for each mutation region is the desired standard within a laboratory. This standard requires the use of two independent methods with non-overlapping primers, when possible depending on the genomics region, between the two assays to minimize allele dropout due to unforeseen polymorphisms in individual samples (Ramirez et al. 2017, 2018). If two different methods are not possible, the laboratory must ensure that the two primer sets used in PCR do not contain significant sequence overlap.

Shaffer LS 2018

On this same topic, regarding microarrays (SNP chips testing 150+ diseases)

Even if the microarray or method provides for more than one probe to a particular target, because the probes are interrogated on a single device and performed at the same time, subjected to the same methods and conditions, these platforms do not meet the desired standard as published (Shaffer et al. 2018), nor do they meet the requirements of methods-based proficiency testing (Schrijver et al. 2014). To comply with the standards, laboratories providing such services must develop a second test on a different method that can be used as an independent, confirmatory test to provide a level of diagnostic testing that can identify allele dropout or nonamplification of certain alleles (Ramirez et al. 2019) and to meet the desired standard, or if the confirmatory test is not available or not conducted, then the testing must be labeled as a genetic screen rather than a diagnostic test to conform to the standards (Shaffer et al. 2018). These direct to consumer tests should be labeled clearly as a genetic screen on the laboratories’ websites so that the veterinarian, dog owner or breeder understands that no irreversible decisions (such as spay, neuter or euthanasia) should be made on the basis of such testing.

Clinical validation: Is this testing proven to be a reasonable marker for disease? Has enough research been done to show this is relevant to the breed(s) it would be offered to? (-This is an excellent question, considering the second scenario above in which the Toy Poodle was tested for a disease not affecting its breed.-)

Analytical validation: Direct from the paper – “The analytical validity of a test is defined as its ability to accurately and reliably identify a mutation of interest in the sample type that will be used clinically. Laboratories must validate their in-house assay for each mutation regardless of what is stated in a peer-reviewed publication.”

Customer education and counseling: Laboratories should have educational material available to help breeders and owners understand their results and how to use them appropriately. For example, if the dog is a carrier for a recessive, is it okay to breed it to a clear? (Yes.) What about in the case of a dominant gene that has incomplete penetrance, as is the case for vWD? (Depends.) There should also be education about whether it is appropriate to test a dog for a mutation; for example, it isn’t appropriate nor ethical to recommend to test a Toy Poodle for a mutation only known to be associated with DCM (not causative) in a single highly dissimilar breed, Dobermans.

In Summary:

Recommendations by testing companies for which tests are appropriate for each dog should be ethical.Testing for inappropriate genetic mutations not known to affect a breed could cause problems in breeding and vet care decisions if a dog is found to be a carrier for a gene associated with a disease not known to affect its breed.

Tests should have multiple steps to prevent inaccurate interpretations, including two independent methods of testing, independent validation of each mutation, and appropriate flow of the workspace and controls.

From the article: “The results from genetic testing are often used by breeders and veterinarians to make decisions regarding spay, neuter and euthanasia. As such, laboratories should desire the highest accuracy possible.“

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post