Contributing positively to the future

Dogs within purebred gene pools are by their very nature related. At some point within the formation of the breed, there were identical ancestors in each dog’s pedigree. What is most important for these closed gene pools is the safeguarding of the existing biodiversity, or genetic variation, within the breed. As gene pools shrink, dogs become more closely related to one another, inbreeding increases, and often times health and longevity in the breed simultaneously decreases. It’s well known that increased inbreeding can reduce litter size and some studies have shown that individual dogs with lower inbreeding levels live longer. So, we work to preserve our biodiversity to prevent the rise of breed specific diseases and to maintain our breeds for future generations.

First of all – what is biodiversity?

The best explanation I’ve yet read is from BetterBred Founder Natalie, and as a result we will share it again here!

Most breeders think of DNA as coming in two options- a good gene, or a mutant gene – like it is in many DNA tests. In fact, there are many genes or (in this case) markers that come in a great many variations – like a t-shirt that is available in different colors. The more variants there are, the more information we have about population genetics. In more inbred breeds, there are fewer variants for each marker. So an inbred breed might have only a few colors available in t-shirts, whereas a diverse breed will have many colors of t-shirts. Apart from the relatively small number of genes that make up specific, visible breed traits, the rest of the gene pool is generally healthier when there’s lots of variation.

Unfortunately when breeders select too strictly for too long for very specific traits, there can be an unintended loss of variation in the parts of the DNA that thrive with more variation. A good way to assess whether that good variation has been impacted is using the markers found in the VGL canine diversity test. Because they are considered neutral – or not associated with any specific known trait – they are great for assessing genetic diversity. In breeds with ample diversity, there will be lots of variations for each marker (lots of colors in the t-shirt drawer).

But what if you have a breed without much variation? Well, this happens, and can happen quite often. In this case the best thing breeders can do is try to make sure the variants that are in the breed are well distributed – so there are plenty of all of them in the breed. Imagine a t-shirt drawer with lots and lots of red t-shirts and only one blue one and one green one. If you lose one of the red ones, it doesn’t change much about the t-shirt drawer – there are lots of other red ones. But if you lose either the blue or green one, the variation is seriously diminished. If, on the other hand a third of the shirts are red, and a third are green and a third are blue, then it’s a lot harder to lose the existing variation in the drawer, even if you lose one once in a while and even though there are only 3 colors.

But being a purebred dog breeder is not so simple as breeding for genetic diversity. Each individual breeder has purpose and goals for their lines – be that attempting to produce stable temperaments for service work or dogs with the right structure to really shine in the conformation breed ring. A breeder must balance risk of health issues found via pedigree research alongside selecting for the breed type and temperament that they so love in their family of dogs. It’s a lot of balls to keep in the air and certainly an art form. No breeder chooses to contribute to a breed for long who lacks passion and perseverance, because breeding is not for the faint of heart.

But IF we are to incorporate genetic diversity alongside all our other spinning plates, what should be the goal? We want to preserve our existing biodiversity, or genetic variation at the breed level, while also reducing inbreeding levels. We do this by not only choosing unrelated breeding mates, but also by selecting for dogs that are less related to the rest of the breed than the average, and dogs that have genetics that are less well represented for that breed. These values on our website are called AGR (average genetic relatedness) and OI (outlier index) respectively.

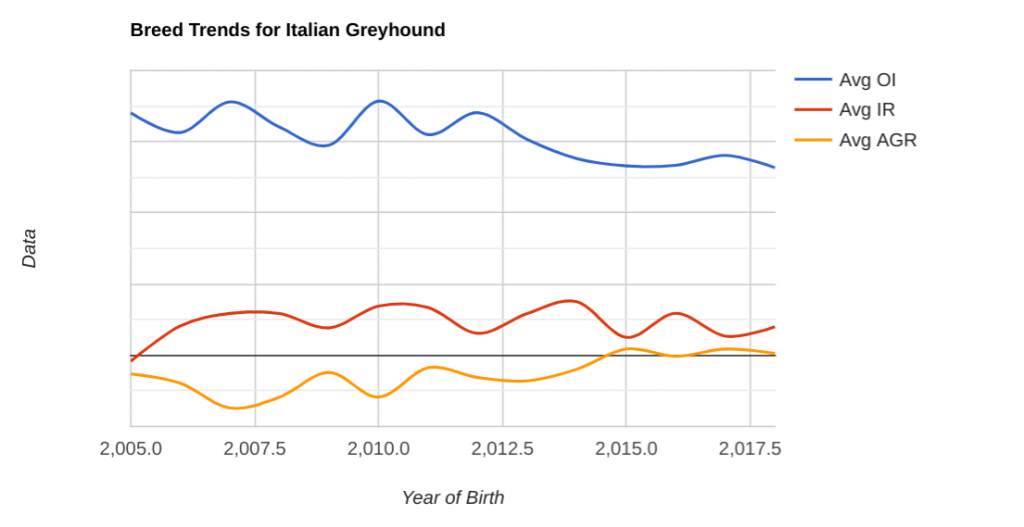

What happens when we do not make decisions that align with the above goals? Dogs within a breed become more and more closely related to one another, they begin to carry the same well represented genetics, and with that loss of variation, breed health suffers. Let’s take a look at a breed’s genetic changes over time. In the image above, we can see the trends within the Italian Greyhound population over time by date of birth. There is a clear trend that dogs within this population are becoming more closely related. You can see this by observing the AGR line. This line is trending upwards; as AGR becomes more and more positive, dogs within each year of birth are becoming more and more genetically similar to one another. This is also shown by OI. The trend in OI shows a clear decrease in the average OI per year. This means that with each year of birth, dogs are carrying more of the same well represented genetics in this population – meaning that the variation within the breed is decreasing. (Wondering what is the trend in your breed? Visit your breed’s breed page and click on “genetic summary”.)

So, how would a conservation breeder select their breedings to help halt or reverse the trends we are seeing?

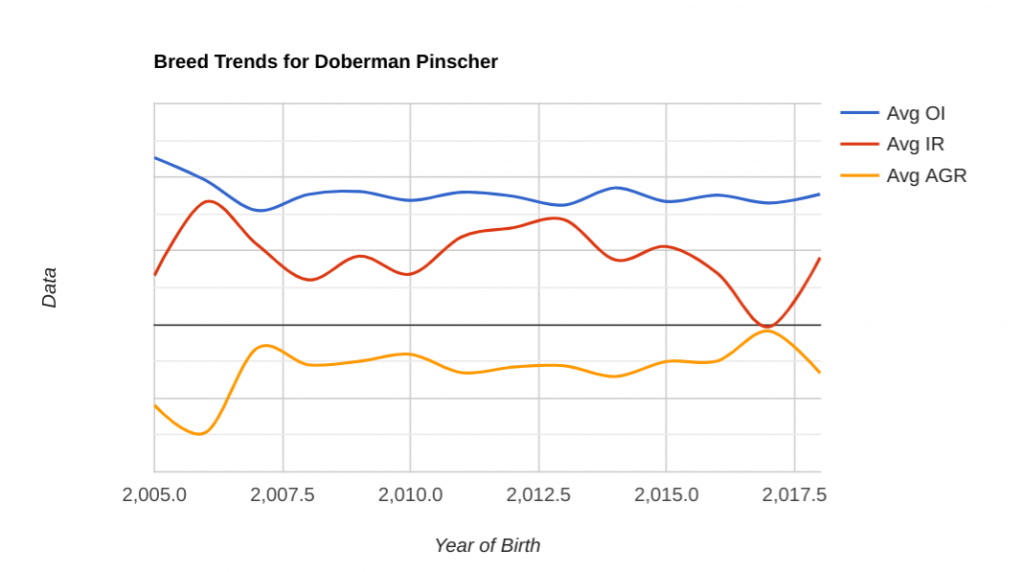

The Doberman Pinscher

The Doberman population is one whose population has become highly related to one another, with most dogs carrying the same few well represented genes. Average lifespan has dropped to 7 years and many of the breed are at risk of dilated cardiomyopathy, which one recent study suggests is mediated in part by autoimmune disease. As you can see from their breed trend, dogs are becoming more closely related, and the breed’s Outlier Index appears to be dropping. This breed desperately needs many working together to improve breed health and preserve the existing biodiversity found in this breed by better distributing it.

Despite the current genetic status of this breed, there seems to be ample diversity found in a handful of dogs or lines. We often talk about two numbers, average alleles per locus and average effective alleles per locus. When looking at the number of alleles found, we consider these two things: the average number of alleles found in total (Na = average alleles), and the average number of alleles that are effectively contributing to the population (Ne = effective alleles). Going back to the t-shirt analogy mentioned above, say we have 10 t-shirts…. 8 of them are red and one is green and one is blue. The total number of shirt colors is 3, however the majority color is red, therefore our “effective” t-shirt color would be only 1. On average, the Doberman Pinscher has 7.58 marker variations found at each tested locus (Na = 7.58). BUT, the breed is essentially only using 2.3 versions of those markers. Ne = 2.3!!!! We will talk below about what one could do with a breeding and selection of subsequent puppies to help slowly reverse this disconcerting finding in this breed.

A test breeding

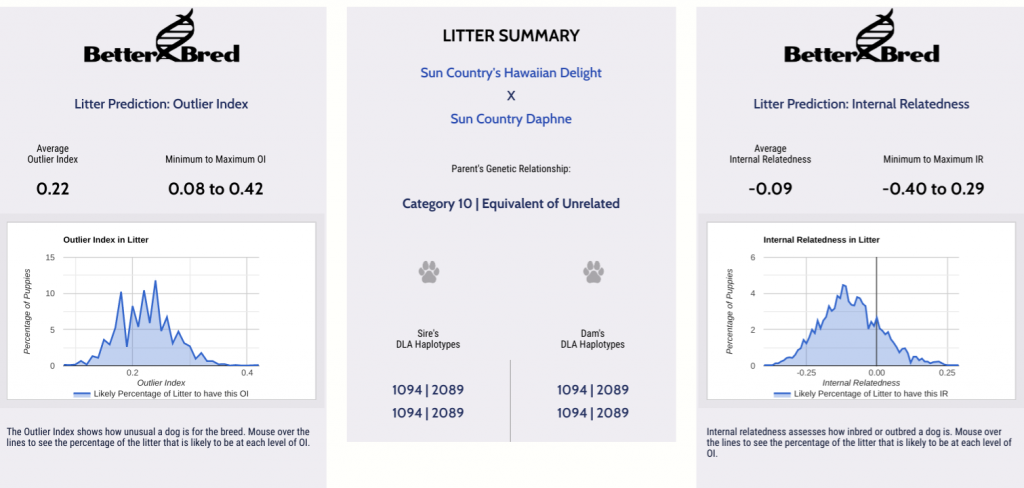

We asked in our BetterBred.com members group for “volunteer” dogs and bitches to run test breedings. We were offered any Sun Country Doberman for our analysis. Curious, I searched all the names public in our database and looked for the male and female that had the least well represented genetics in the population in the list (aka the highest OI). I found “Sun Country’s Hawaiian Delight” and “Sun Country Daphne“. Both of these two dogs have Outlier Index values well above breed average, meaning they are atypical in relation to the rest of the breed. If they are unrelated, their breeding would go towards redistributing the genetic variation this breed has to offer.

After visiting each of their profiles and looking over their genetic results (to learn what each profile means visit here!), I used our comparison tool to see how closely related they are to one another. Our handy comparison tool is a free feature on our website, and it can give you an idea how a pair of dogs (no matter the gender) might look compared to one another. In this case, the dogs are a category 10! Huzzah! Time to run the test breeding!

Test breedings can be run in two ways on our website. You can hover over “Dog Search” and find the test breeding option in the drop down, or you can visit the potential breeding lists, the link to which is found under each dog’s profile. In this case I went to the breeding lists and easily found the mate in the list and then simulated the litter. How does it look??

In breeds like the Doberman Pinscher, in which the inbreeding levels are high and the gene pool is restricted with a genetic bottleneck, even unrelated breedings can result in high inbreeding levels – because all relatedness measures are relative to the context of the breed. As mentioned above, all dogs in the same breed are somewhat related, some more so and some less so. Happily, in the case we see here, the inbreeding level predicted for this breeding is low, with very little of the litter falling at the high inbreeding level of .15. You can see this by looking at the graph on the right above, which shows the expected distribution of inbreeding levels for the puppies in a litter. We see the majority of the litter would fall below 0; this is fantastic, especially in this breed. Reducing the levels of inbreeding will theoretically lead to larger litters and improved longevity in the puppies.

But don’t forget biodiversity! Focusing only on reducing inbreeding will actually lose breedwide biodiversity overtime, which is why BetterBred has other measurements to consider. What about redistributing the biodiversity of the breed? The average Outlier Index for the litter is .22, a number hard to reach within this breed. The breed average is .17 and dropping! You can see the predicted distribution of puppies for this litter in the graph on the left above, while the puppies are on average .22, we see also many can fall above this value as well (and many can fall below, in the more typical range for this breed). As long as the puppies selected from this breeding were at or above the predicted average for the litter, the breeding will be well on its way to improving the genetic state of the Doberman. Add to this the fact that most of the puppies will be outbred on average, this is wonderful! Imagine if many breeders used this tool together, how much could the population change for the better in one generation?

Are there any pitfalls in this breeding? Sadly when we look at the DLA, or dog leukocyte antigen – the dog’s immune system – we see that all puppies will inherit the very common DLA haplotype for this breed, 1094 paired with 2089. However, 77% and 78% of the breed’s haplotypes are these, so it’s extremely difficult to breed for diverse DLA.

All in all, this breeding would contribute to the improvement of this breed’s genetic status. Of course, breeding is about more than the numbers, so the individual breeder would need to assess the worthiness of each pairing based on type, temperament, pedigree risks, drive, etc., as per the breeder’s goals as we always have before.

Conclusion

Breeding for genetic diversity is a tricky business when we take in to account all the aspects we already consider as conscientious breeders. However, we must also be aware that our breeding choices impact the future genetic status of our breeds and each breeding decision will contribute positively or negatively for our breed’s future. Preservation breeding requires breeders wearing many hats, and we salute those of you working for your breed’s tomorrow.

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post